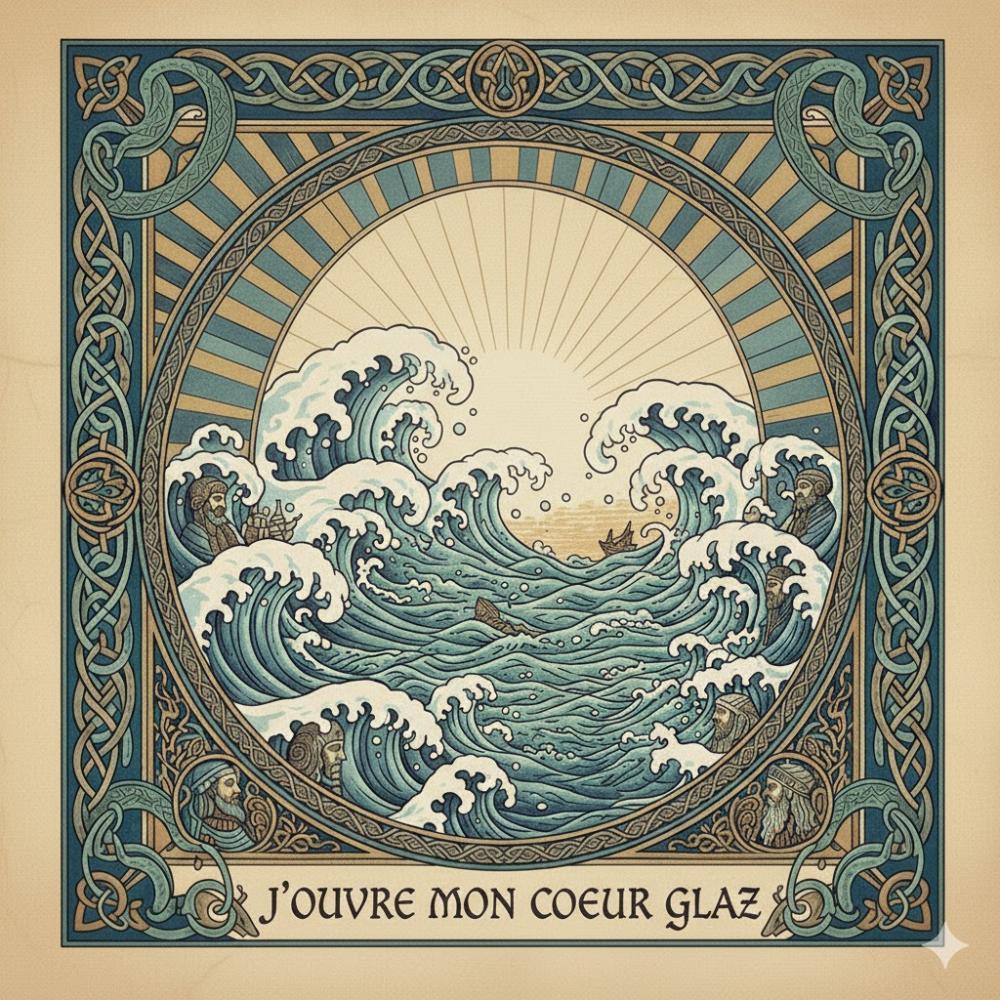

"Glaz": blue, green, or gray. The identity of Brittany is a color. This color is that of the stormy sea.

"Glaz": blue, green, or gray. The identity of Brittany is a color. It is that of the tempestuous and metamorphic sea — a sea-interface, a bridge thrown over the abyss to shape a "Finis Terrae" that is not a mourning, but a dawn. It is there, at the mercy of the waves, that the terminus of human migrations is drawn, facing one of the oldest cradles of humanity: Menez Dregan, anchored in granite for four hundred and fifty millennia.

The ocean here is the "Mare Nostrum," whether it calms in the English Channel or thunders in the Atlantic. From the dawn of the Neolithic, it opened the first routes of exchange, transforming the shore into a border between worlds. The boat, engraved in the mineral silence of the dolmens, was not merely a fishing or trading vessel; it stood as a psychopomp ship, a sacred passage between the light of the living and the shadow of the ancestors — a path of the dead to the beyond.

From this primordial foam was born the destiny of the "little princes" of the Bronze Age, making Brittany a "land of the Celts." Mor Breizh was the kingdom of leather and wooden curraghs, fragile skiffs whose taut skin vibrated to the rhythm of medieval swells, carrying saints and kings to Armorica in a single night of faith. It is the time of legendary founding saints, Gwen and Fracan, Enora, Pol, Samson, or Tugdual, whose names still resonate in the stone of the parishes.

Later, during the Age of Exploration, Brittany asserted itself as the "Peru of the French," drawing its fortune in the wake of the great sailing ships. It is the rise of maritime cities and the epic of the Renard, the last corsair from Saint-Malo defying the crowns; it is finally the morutières schooners plunging into the frost of Newfoundland. For long before Jacques Cartier raised anchor in 1534, Breton sailors were already haunting the waters around Iceland, etching their wake in the vastness long before official history seized it.

Today, this lineage of giants continues on the Routes du Rhum, where the wake of Éric Tabarly and Florence Arthaud continues to tear through the horizon, transforming offshore racing into an art of living. This same thirst for elsewhere is written each year on the quays of Saint-Malo, at the "Étonnants Voyageurs" festival. Founded in 1990 by Michel Le Bris, it has made the corsair city the home port of a "world literature" where the book becomes a sextant. The Book Fair then becomes a compass to explore the intimate of the "Glaz," reminding us that Brittany is, by essence, a land of departure and stories where the verb unfolds like a sail.

But the sea is also the "Bag Noz," the Reclaiming Sea. Shroud of the Veneti fleets, wake of the Viking drakkars plundering Landévennec, or the black wound of the Amoco Cadiz. It is the one that swallowed the ephemeral city of Ys and the princess Dahut. In the foam lurks the Ankou, and the shadow of the wreckers was long the tragic double of the seaweed harvester bent over the foreshore. Yet, it is in this tension — between the call of the open sea and the rooting to the ground — that the Breton heart beats. This land exhales iodine, and the cry of the seagulls crashes against the clinking of slates under the drizzle. The sea owes everything to the land: it is she who lent her farmers to pour them onto the waves.

This Brittany is not a postcard. It is a breath born of Gallo and Breton, a popular nation of "daughters" and "sons of bumpkins" transfigured into princesses and princes of a universal Atlantic culture. Against the smoothing of algorithms, it still protects the fairies of Sylvain Tesson, guardians of a magic that refuses to fade. Anjela Duval, a peasant-poetess of the Breton language, was one of those whose verb plunges its roots into the furrow.

This sacredness finds its ultimate resonance in song. If the sea is its body, music is its cry. Between Pierre-Jakez Hélias, the land in the belly, and Xavier Grall, the wind at the forehead, we walk on a ridge line, between the "Horse of pride" and the "Lying horse." Alan Stivell has awakened the universal harp of the Celts, the bard Glenmor has roared like a stone prophet, Dan Ar Braz makes the stars dance, and Yann Tiersen makes the granite of Ouessant vibrate to the rhythm of his piano. These are also the ancestral voices of the Goadec Sisters, Maryvonne Le Flem, or Andrea Ar Gouilh, or those, inhabited, of Nolwenn Korbell and Denez Prigent where resonates the soul of a people that has managed to save its laments from oblivion.

Brittany is indeed a land of elsewhere. It is this absolute "Glaz": a hue that escapes capture, a flight that never renounces itself, an eternity that begins anew with each tide. One then understands why paddle signs were engraved in the covered alley of Mougau-Bihan in the heart of the Monts d'Arrée. Armorica is this point of balance: a piece of the world in the middle of the ocean, a legend battered by the winds, but standing firm against time. It is a vibrant land, rich in its History and open to the world. A Brittany that is "Armorica," literally: "the land in front of the sea."

Bloavezh Mat.

Mikaël

Commentaires (0)

Aucun commentaire pour le moment. Soyez le premier à réagir !