The study of the signs engraved on the megalithic monuments of the Atlantic façade, particularly in Morbihan, reveals the existence of a highly coherent symbolic system, reflecting a deep and shared mythological culture in the Neolithic. The recent interpretation, shifting the analysis from a purely agropastoral framework to a maritime and celestial context, allows for the deciphering of a complex narrative, a true "path of the dead" inscribed in stone.

A mythological culture of engraved signs on neolithic megaliths: the Atlantic grammar of a "path of the dead"

The study of signs engraved on the megalithic monuments of the Atlantic facade, particularly in Morbihan, reveals the existence of a highly coherent symbolic system, testifying to a profound and shared mythological culture during the Neolithic. Recent interpretations, shifting the analysis from a purely agro-pastoral framework toward a maritime and celestial context, allow for the deciphering of a complex narrative—a true "path of the dead" inscribed in stone.

A grammar of engraved signs common to the Atlantic

The first attempt at an inventory was conducted in 1873 by Gustave de Closmadeuc in his pamphlet entitled *Sculptures lapidaires et signes gravés dans les dolmens du Morbihan*. This approach was expanded by the British archaeologist Alasdair Whittle who, in 2000, suggested a link between certain signs and the marine environment. This hypothesis was reinforced and refined by Serge Cassen and Jacobo Vaquero, who identified the cetacean represented as a sperm whale (Cassen and Vaquero, 2000), thus placing maritime symbolism at the center of the analysis. The inventory of motifs reveals a series of key symbols:

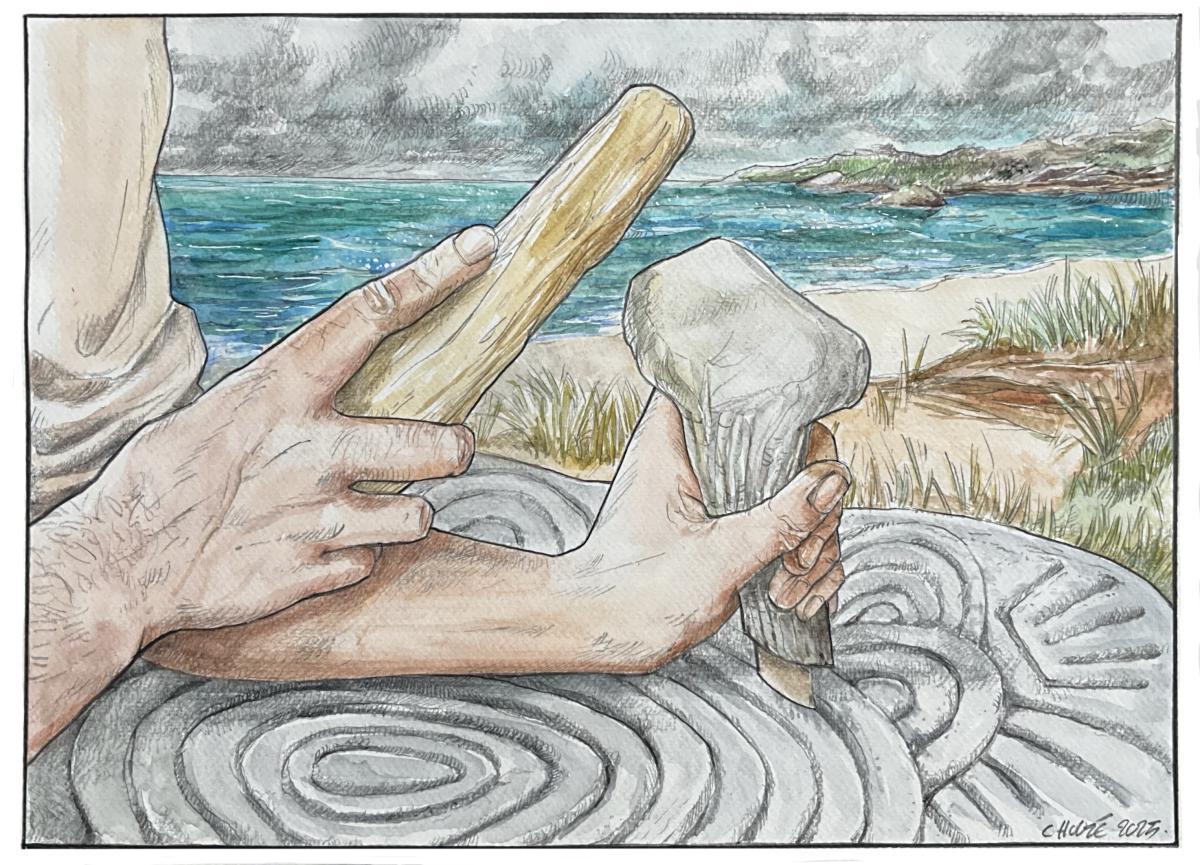

- The polished axe sign: This was the preferred object of the first land-clearing efforts. It is represented on megaliths, either hafted (with a handle) or unhafted. Jean-Loïc Lequellec emphasizes that "the hesitation between axe, hammer, mallet, and club can be explained by a linguistic derivation from the same pre-Indo-European referent '[stone] weapon', to be understood within a Neolithic context" (Lequellec, 1996). The isolated polished axe blade "suggests that the lithic part of this object was sufficient to carry the meaning" (Lequellec, 1996), these signs constituting the invariants of an etiological foundation myth and a form of proto-writing. Jean-Loïc Lequellec also draws a parallel between the polished axe sign and the *mel beniguet* or "blessed mallet" which ensured a good death in folk traditions in Brittany. Z. Le Rouzic, in 1939, had also been interested in the question by examining hammer-shaped stones from the village of Notério in Carnac and the chapel of Saint-Germain in Brech (Z. Le Rouzic, 1939).

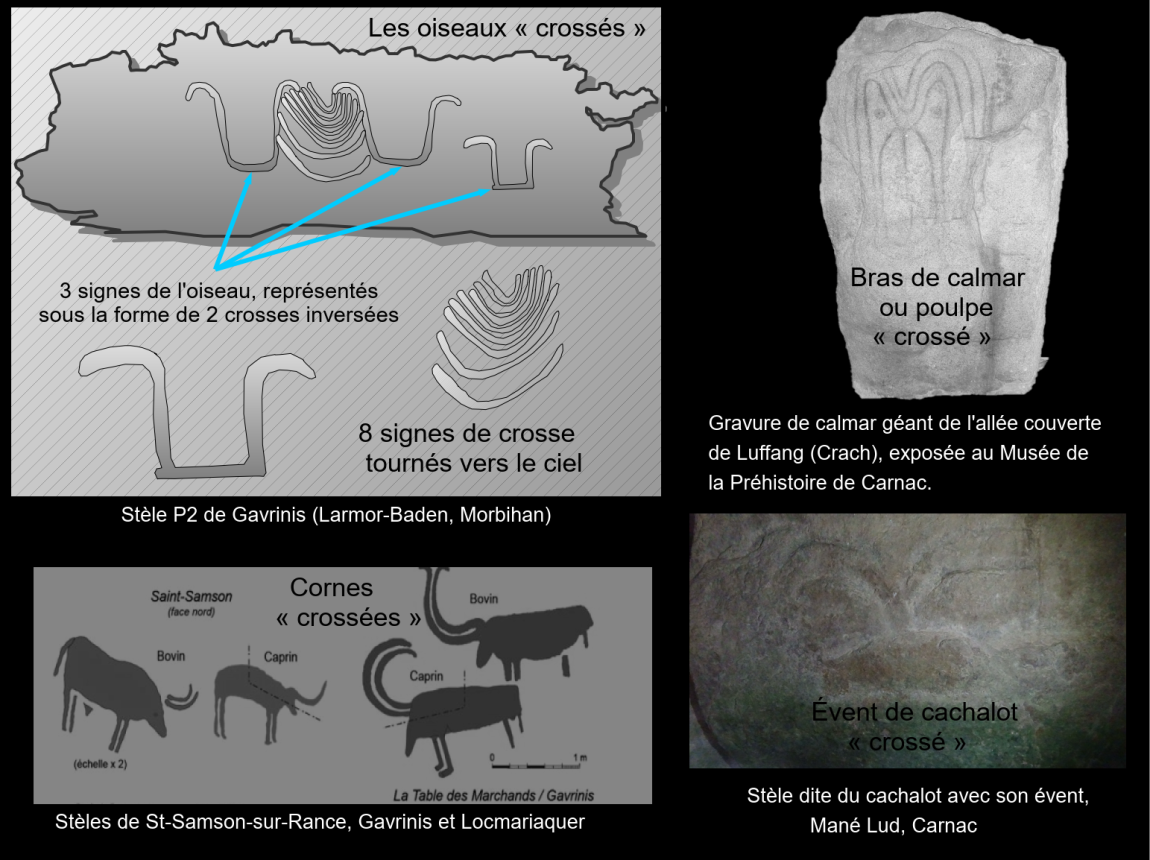

- The crozier (crosse) sign: Its shape is compared to the Etruscan *lituus*, the ritual tool used to demarcate the templum or "celestial temple." This sign of the crozier is also close to the heqa (scepter) of the pharaohs in Egypt or the *âmâat* (throwing sticks) for hunting marsh birds. The insignia of the heqa is often represented crossed with the flail (*flagellum* or *nekhekh*), considered a symbol of protection and fertile power. The association of birds and croziers on the P2 slab of Gavrinis seems comparable to the practices of augurs.

- Representations of boats: They embody initiatory journeys and crossings of the afterlife, with precise narrative patterns, as at Mané er Groez in Kercado, with 5, then 4 and 3 anthropomorphic signs.

- Animals: Domestic and wild fauna appear alongside the cetacean.

The combination of the hafted axe with the crozier (*lituus*) is a powerful symbolic abstraction that can have no other necessity than ritual. It could serve to anchor a territory in the afterlife by delimiting a break in planes. Animal attributes (horns, blowholes, giant squid tentacles) are figured in the manner of croziers, projecting the "croziered" objects and animals into a celestial ritual dimension, testifying to a shared codicology and mythological culture. Thus, the slab covering the burial chamber of Gavrinis features on its upper face a bovid figure whose horn tips take the form of two inverted croziers, and the horns and spine of the caprid are two radiated arcs.

Some symbolic associations can be highlighted. Thus, a focal point of the menhir of Saint-Samson-sur-Rance is emphasized by two crozier signs associated with the sperm whale sign, appearing to draw a map of the sky, from Ursa Major toward the north pole.

On the contribution of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism

A set of symbolic correspondences. All these signs translate a language that can be presented in its elementary or developed form. Structuralist analysis, inspired by Claude Lévi-Strauss, allows us to grasp the internal logic of this visual language through correspondences associating the stylized hafted axe, a quadrangular shape, and a crescent (the boat) (Cassen, Serge, Grimaud, Valentin, Lescop, Laurent, Cadwell, Duncan, 2005). These symbols refer to three fundamental dimensions: terrestrial (the square), celestial (the stylized polished axe, croziered or not), and cosmic (the boat).

This elementary visual language is found at megalithic sites such as Spézet (Finistère), Vieux Moulin at Plouharnel (Morbihan), the Table des Marchands at Locmariaquer (Morbihan), or Portela de Mogos and Vale Maria do Meio in the Alentejo of Portugal. The program can also be developed into a full narrative schema as at Mané Lud or Gavrinis in Morbihan. The great menhir of Locmariaquer, reconstructed from the ceiling slabs of the Table des Marchands and Gavrinis, seems

Commentaires (0)

Aucun commentaire pour le moment. Soyez le premier à réagir !